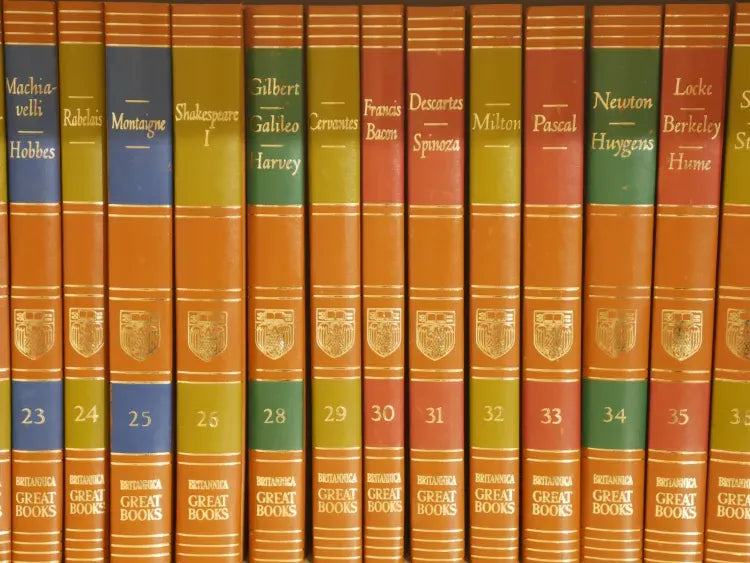

I was raised by intellectuals. The Great Books of the Western World my lone inheritance. Orange sap in the book spines, the remaining evidence of the Marlboro 100s, packed tight in those golden embossed boxes, my parents smoked nonstop, in the bohemian dens in which I was fermented. As their only child, they raised me to speak their language. By middle school, I could tell you about Marshall McLuhan and Wittgenstein and how he shaped our understanding of semantics, but my college roommate had to teach me how to use a razor to shave my face. My dad could and still does in his Assisted Living take on whole rooms at Trivial Pursuit - it is and has always been his parlor trick - but he never seemed to notice that his toenails were curling in his shoes. I love my parents, and I’m finally old enough to cherish the memory of their quirks with fondness. I miss my mother, who passed away in 2021, every day. I’m eternally grateful for the intellectual firepower they armed me with. But like much of the knowledge we cultivated as a family, it did little to ease our souls.

They must’ve thought the hospital switched their baby. What is this tactile creature? Who jumps onto our bed and dives off the porch into the potted cactus spines? We used to call it hyperactivity, but nowadays, I suspect, they’d shove Ritalin down my throat to sit still in my school desk, like a duck being prepared to be foie gras. I don’t think they knew what to do with me. They tried to funnel my unbridled physicality into tennis camp at the university where my mother worked, but I was more interested in surfing and jumping off picnic tables on my skateboard. We spent a lot of time in Emergency rooms, though my parents never complained, taking alternating smoke breaks in the parking lot. The only time I heard my dad speak of exercise was to share the news that the guy who invented jogging died of a heart attack, as if his refusal to exercise (aside from a pretty stellar flat-arched jump shot in the garage-mounted basket) was reaffirmed by this tragedy.

They were nervous, agitated, and on occasion paranoid. If there are emojis for existential and anxious, they would adorn our family crest. They drank a lot when I was young, and then when they quit as a team, they soothed their sympathetic nervous systems with tranquilizers. Valium and Xanax more readily available in our home than multivitamins. I am reminded of an NPR story about Sylvia Plath that described her as someone who had a constant awareness of her own mortality. This was the frequency at which I was weaned, and probably why I remember this fact included in a public radio segment from twenty-five years ago.

My grandfather passed away before my father’s tenth birthday, and so my father never imagined a world in which he lived past the age of 40. He’s 80 now, and a case might be made that smoking two packs a day and avoiding exercise is a recipe for longevity. He’s outlived much of his own family. That said, I can’t imagine he’s ever felt good physically. It took a few years of rigorous meditation and a few thousand miles in my trainers to control my own low-grade fever of dread. Overcoming that lifelong sensation, those creeping feelings that darkness was imminent, is liberating. It’s no coincidence that many of the teachers who brought Buddhism to the West were Jews whose parents had survived the Holocaust. We Jews are attuned to the frequency of suffering, and therefore, many of us find solace in the soundtrack Buddhism is broadcasting. There’s a lot of talk these days about generational trauma passing down. I blame Buddhism first and foremost for feeling comfortable in my skin, even if it took forty years to get here.

My mother’s mental health was so volatile that no sharp knives were allowed in our home. Although I didn’t know any different until I got married and Jen and I would assist with making holiday dinners at their home with the lone steak knife remaining from the set they received for their wedding. It carried a heavy burden, that wooden handled steak knife, bowed from decades of overuse - responsible for opening packages, cutting chicken and screwing in loose screws. Sharp blades and loaded weapons are a regular part of owning a farm and protecting your livestock. And in Judaism, it is not kosher to take an animal’s life without the sharpest and quickest of actions. I feel comfortable that I may live amongst weapons responsibly without the fear that I will become a self-immolating somnambulist. That wasn’t always the case. When you grow up in a bipolar home, you begin to suspect that madness is contagious or might be accidentally inhaled like a spore in The Last of Us.

It was not until I confronted my own battle with anxiety in my thirties that I realized that exercise was a perfectly acceptable form of self-medication. Quitting smoking before we had children came with its own wave of anxiety and sadness. Given my upbringing, I have always steered clear of pills. So, I ran until my nervous system was subdued. On the beach, along the riverbed, through the park, and for many years barefoot along the boardwalk. Then, suffering from a debilitating case of piriformitis, Jen convinced me to attend a yoga class with her. There, I learned to practice patience and taste-test calmness for the first time on my rubber mat. It was through that world that I was set upon the path towards contentment. But that practice, on the mat and on the zafu, is just that - practice. Not so we get really good at twisting ourselves into knots, but so we can apply our attention with intention off the mat, at the bank and grocery store, where a flickering neon bulb on a hot summer day, no longer causes me to fight or flight my way back to my car in the parking lot. Now, I remind myself to breathe, still annoyed with the buzzing neon light, but with the understanding that the sensations I am experiencing aren’t a matter of life or death. Having the tools to recalibrate the frequency at which we find ourselves suffering is a tremendous gift. I wish every being could experience what I fear my mother never could in her lifetime.

The middle way. That’s what the Buddha called his path. Between the ivory walls of the Kingdom where he was born and the river shore, where he spent his days as an ascetic, he discovered a sweet spot smack dab in the middle. That’s what I’m hoping for. An existence where physicality and the knowledge of the Great Books of the Western World can coexist. I believe the farm is the perfect medium for that life. Where digging ditches and returning home with dirty nails give way to quiet nights like these on my keyboard. There was a moment earlier, when I found myself alone at the bottom of our market garden, the farm workers had all gone home, and I could hear the bees on their superhighway, high above me, rushing back and forth from the citrus orchard to their hive. There was a time in my life when I wouldn’t have noticed; distracted by the dialogue on permanent spin cycle in my mind.

My parents were (and my father still is) some of the most intelligent people I have ever met, but they struggled their whole lifetime to experience lasting joy. I believe a place exists for all of us, where intellect and physicality can be put to use to bring about a better world. That’s the path I’m on, and I will forge forward as long as I am allowed. Doing as little harm as I can to the earth and all sentient beings. Well, except for gophers. Fuck those dreadful critters. Though I promise to bring about their collective demise with as little suffering as possible. 🙏🏽